Celtic Gods and goddesses

credit: Anette Illustrations

Cernunnos

Cernunnos is a horned god found in Celtic mythology. He is connected with male animals, particularly the stag in rut, and this has led him to be associated with fertility and vegetation. Depictions of Cernunnos are found in many parts of the British Isles and western Europe. He is often portrayed with a beard and wild, shaggy hair–he is, after all, the lord of the forest.

With his mighty antlers, Cernunnos is a protector of the forest and master of the hunt. He is a god of vegetation and trees in his aspect as the Green Man, and a god of lust and fertility when connected with Pan, the Greek satyr. In some traditions, he is seen as a god of death and dying, and takes the time to comfort the dead by singing to them on their way to the spirit world.

In Margaret Murray's 1931 book, God of the Witches, she posits that Herne the Hunter is a manifestation of Cernunnos. Because he is found only in Berkshire, and not in the rest of the Windsor Forest area, Herne is considered a "localized" god and could indeed be the Berkshire interpretation of Cernunnos. During the Elizabethan age, Cernunnos appears as Herne in Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor. He also embodies fealty to the realm, and guardianship of royalty.

In some traditions of Wicca, the cycle of seasons follows the relationship between the Horned God–Cernunnos–and the Goddess. During the fall, the Horned God dies, as the vegetation and land go dormant, and in the spring, at Imbolc, he is resurrected to impregnate the fertile goddess of the land. However, this relationship is a relatively new Neopagan concept, and there is no scholarly evidence to indicate that ancient peoples might have celebrated this "marriage" of the Horned God and a mother goddess.

Because of his horns (and the occasional depiction of a large, erect phallus), Cernunnos has often been misinterpreted by fundamentalists as a symbol of Satan. Certainly, at times, the Christian church has pointed to the Pagan following of Cernunnos as "devil worship." This is in part due to nineteenth-century paintings of Satan which included large, ram-like horns much like those of Cernunnos.

Today, many Pagan traditions honor Cernunnos as an aspect of the God, the embodiment of masculine energy and fertility and power.

Source: https://www.learnreligions.com/cernunnos-wild-god-of-the-forest-2561959

credit: Anette Illustrations

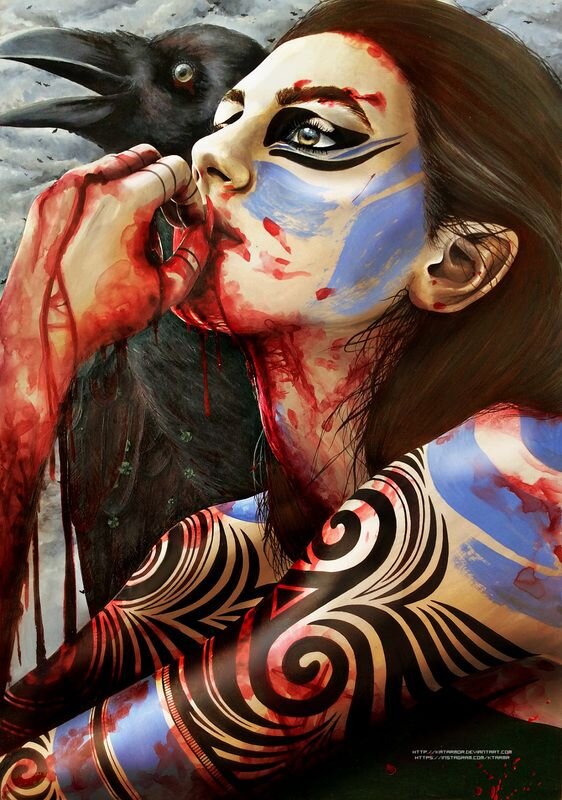

Morrígan

The Morrígan is most well known as an Irish Goddess who often appears in crow or raven form, and is associated with battle, warriors, sovereignty, prophecy, and Otherworld power. Though early source literature referencing Her only exists in Irish, folklore and archaeological records suggest that She, or closely related divinities, were known and worshiped in Britain and Gaul as well, suggesting that we have in Her a pan-Celtic Goddess.

The Morrígan’s name translates from the Irish as ‘Great Queen’ (from Old Irish mór=great and rígan=Queen). This name is a key to Her nature, showing that sovereignty and queenship are core aspects of Her identity and power. Some scholars have given the name an alternate etymology, translating it as ‘Phantom Queen’ (from proposed Proto-Celtic *mor, connoting terror/nightmare, or *mar, connoting the dead). It should be noted that popular etymologies interpreting the Morrígan’s name as connoting ‘Sea Queen’ (via the Welsh mor=sea) and connecting Her to the Arthurian character Morgan le Fay, are incorrect.

As one of the Celtic sovereignty Goddesses, the Morrígan has an association with the land itself, and the rulership and protection of the land and its people. Her seasonal appearances are linked to rituals of warfare and sovereignty as they appear to have been practiced in early Irish society. Archaeological and literary evidence suggests that her earliest manifestations may have been as a tribal/territorial Goddess, and that Her war-bringing and martial functions arose out of this sovereignty and tutelary role.

As the Morrígan is best documented in the Irish literature, reflecting early medieval perceptions of Iron Age Celtic society, a cattle-raiding warrior culture, we know Her best as a Goddess of battle, heroes, and the dead. The Morrígan is deeply associated in Her source lore with incitement of heroes toward glory in battle, with the granting of victory, and with their deaths; in Her own words, She says to the great hero Cú Chulainn, “I am guarding your death.” In battle, She takes part in the action primarily through the use of sorcery, Druidic magic, shape shifting, terrorizing the foe, and giving aid and strategic information to Her people. She shape shifts into many forms in Her tales, including crow and raven, cow, wolf, eel, and both old and young women. She also appears as a sexual figure, offering victory and prophetic aid to Her chosen war-leader with whom She mates. She also fulfills important roles with regard to poetry and prophecy, giving poetic incitements to the heroes of the Tuatha Dé Danann to rise to their hour of need, giving prophetic pronouncements of victory or of doom on the eve of decisive battles, and announcing the victories and the tales of great deeds afterward.

A common perception of the Morrígan is that She is a form of ‘the Triple Goddess’. While it is true that in many instances where She appears in the Irish literature, She is described as being one of three ‘sisters’, or is referred to as a trinity directly, it should be understood that the triplicity of the Morrígan is NOT equivalent to modern Wiccan ideas of ‘the Triple Goddess’. The Morrígan cannot be neatly fit into a modern ‘Maiden-Mother-Crone’ trinity based on a rigid model of female reproductive status, nor should we attempt to force Her into that model.

Triple-formed deities are very common in Celtic religion. We see examples of this in the three sovereign land Goddesses of Ireland, Ériu, Banba, and Fotla; in the Three Gods of Skill; in the Three Craftsman Gods; and in the Matres or Matrones, Gaulish Celtic Goddesses appearing in groups of three. In each of these examples and many others, the three members of the triad to fulfill related roles as part of a single primary functions. For the ancient Celts, operating within a triune cosmology (land, sky, and underworld/sea), to frame an identity or concept in a triune form conveyed totality. Thus, triads of divinities represent the totality of a set of divine roles or functions, individualized into three characters.

In the case of the Morrígan, it does not work to neatly classify Her epiphanies into three distinct identities or faces; for many different names appear in these triune groupings (Morrígan, Badb, Macha, Némain, Féa), and there is not complete consistency in which three appear and how they are described in the literature. Certainly, not one of these Goddesses or aspects of the Morrígan can be neatly identified with a Maiden, Mother or Crone archetype.

source: https://www.corupriesthood.com/the-morrigan/

credit: Anette Illustrations

Brigid

Perhaps one of the most complex and contradictory Goddesses of the Celtic pantheon, Brigid can be seen as the most powerful religious figure in all of Irish history. Many layers of separate traditions have intertwined, making Her story and impact complicated but allowing Her to move so effortlessly down through the centuries. She has succeeded in travelling intact through generations, fulfilling different roles in divergent times.

She was, and continues to be, known by many names. Referred to as Bride, Bridey, Brighid, Brigit, Briggidda, Brigantia, I am using Her name, Brigid, here. There are also many variations on pronunciation, all of them correct, but, in my own mind, I use the pronunciation, Breet.

Brigid is the traditional patroness of healing, poetry and smithcraft, which are all practical and inspired wisdom. As a solar deity Her attributes are light, inspiration and all skills associated with fire. Although She might not be identified with the physical Sun, She is certainly the benefactress of inner healing and vital energy.

Also long known as The Mistress of the Mantle, She represents the sister or virgin aspect of the Great Goddess. The deities of the Celtic pantheon have never been abstraction or fictions but remain inseparable from daily life. The fires of inspiration, as demonstrated in poetry, and the fires of the home and the forge are seen as identical. There is no separation between the inner and the outer worlds. The tenacity with which the traditions surrounding Brigid have survived, even the saint as the thinly-disguised Goddess, clearly indicates Her importance.

As the patroness of poetry, filidhecht, the equivalent of bardic lore, are the primal retainers of culture and learning. The bansidhe and the filidh - Woman of the Fairy Hills and the class of Seer-poets, respectively, preserve the poetic function of Brigid by keeping the oral tradition alive. It is widely believed that those poets who have gone before inhabit the realms between the worlds, overlapping into ours so that the old songs and stories will be heard and repeated. Thus does Brigid fulfill the function of providing a continuity by inspiring and encouraging us.

The role of the smith in any tribe was seen as a sacred trust and was associated with magickal powers since it involved mastering the primal element of Fire, moulding the metal (from Earth) through skill, knowledge and strength. Concepts of smithcraft are connected to stories concerning the creation of the world, utilizing all of the Elements to create and fuse a new shape.

credit: Anette Illustrations

Cerridwen

In Celtic Welsh mythology, Cerridwen is a powerful Underworld Goddess, and the keeper of the cauldron of knowledge, inspiration and rebirth. She rules the realms of death, fertility, regeneration, inspiration, magic, enchantment and knowledge. Cerridwen is a shape shifting Goddess, able to take on various forms. She is known as being a white witch or goddess, and is also associated with herbology and astrology.

Cerridwen represents the need for change; that a transformation is at hand. It is time to examine what circumstances in your life no longer serve you. Something must die so that something new and better can be born. You can tap into her ceaseless energy to plant seeds of change and pursue their growth with your own power.

The Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuatha Dé Danann, the people of the Goddess Danu, were one of the great ancient tribes of Ireland. The important manuscript 'The Annals of the Four Masters', records that they ruled Ireland from 1897 B.C. to 1700 B.C.

The arrival of the tribe in Ireland is the stuff of legend. They landed at the Connaught coastline and emerged from a great mist. It is speculated that they burned their boats to ensure that they settled down in their new land. The rulers of Ireland at the time were the Fir Bolg, led by Eochid son of Erc, who was, needless to say, unhappy about the new arrivals.

The Tuatha Dé Danann won the inevitable battle with the Fir Bolg but, out of respect for the manner in which they had fought, they allowed the Fir Bolg to remain in Connaught while the victors ruled the rest of Ireland.

The new rulers of Ireland were a civilised and cultured people. The new skills and traditions that they introduced into Ireland were held in high regard by the peoples they conquered. They had four great treasures (or talismans) that demonstrated their skills. The first was the 'Stone of Fal' which would scream when a true King of Ireland stood on it. It was later placed on the Hill of Tara, the seat of the High-Kings of Ireland. The second was the 'Magic Sword of Nuadha', which was capable of inflicting only mortal blows when used. The third was the 'sling-shot of the Sun God Lugh', famed for its accuracy when used. The final treasure was the 'Cauldron of Daghda' from which an endless supply of food issued.

The original leader of the Tuatha was Nuada but, having lost an arm in battle it was decreed that he could not rightly be king. That honour went to Breas, a tribesman of Fomorian descent. His seven year rule was not a happy one however, and he was ousted by his people who had become disenchanted with hunger and dissent. Nuada was installed as King, resplendent with his replacement arm made from silver.

Breas raised an army of Fomorians based in the Hebrides and they battled with Nuada at Moytura in County Sligo. The Tuatha again prevailed and the power of the Fomorians was broken forever. The victory had cost the Tuatha their King as Nuadha had died in the battle. A hero of the conflict named Lugh was instated as the new King of Ireland.

The grandsons of the next King, Daghda, ruled during the invasion by the mighty Melesians. The Tuatha Dé Danann were defeated and consigned to mythology. Legend has it that they were allowed to stay in Ireland, but only underground. Thus they became the bearers of the fairies of Ireland, consigned to the underworld where they became known as 'Aes sidhe' (the people of the mound - fairy mounds).

The Melesians used the name of one of the Tuatha Dé Danann gods, Eriu, as the name of their new kingdom. Eriu or Eire is still used in modern times as the name of Ireland.

source: http://www.ireland-information.com/irish-mythology/tuatha-de-danann-irish-legend.html

credit: Anette Illustrations

Rhiannon

The Celtic Moon Goddess Rhiannon was born at the first Moon Rise and is known as the Divine Queen of Faeries. She is the Goddess of fertility, rebirth, wisdom, magick, transformation, beauty, artistic inspiration and poetry. Rhiannon manifests as a beautiful young woman dressed in gold, riding a pale horse, with singing birds flying around her head. The singing birds can wake spirits or grant sleep to mortals.

Much of what we know of Her comes from the ancient Welsh folklore book The Mabinogion by Lady Charlotte Guest.

While our riding one day, Pwell Lord of the Kingdom of Dyfed, saw a gorgeous woman dressed in gold and riding a white mare. Pwell chased after Rhiannon, but could not catch Her, no matter how fast he rode. Finally, Pwell called to Her and She stopped. When he asked Her why She had eluded him, Rhiannon replied that he had only to ask Her to stop. Rhiannon and Pwell were married and Rhiannon gave birth to a son called Pryderi. When the infant was three days old, on the night of May Eve, the nurse-maids charged with watching over Pryderi fell asleep. When they awoke they found the baby missing and in a panic smeared puppy blood on the lips of the sleeping Rhiannon and accused Her of killing and eating Pryderi. Rhiannon was found guilty of infanticide and was ordered by Pwell to spend seven years seated at the city gates confessing Her crime to all who approached and then carrying them to court upon Her back.

Meanwhile, a beautiful mare owned by Teyrnon gave birth to a foal every May Eve and every May Eve the foal vanished. He decided to keep watch inside the stable and just as his mare gave birth, a huge clawed hand reached in the window to grab the foal. Teyrnon hacked off the hand with his sword and the foal was saved. Teyrnon ran outside to capture the thief but found no one . When he returned to the barn he discovered a beautiful baby boy, whom he and his wife adopted. After a time the couple noticed that the child had an affinity for horses, had supernatural powers, and had begun to resemble Pwell. Teyrnon deduced that the child was Pwell and Rhiannon's son and so returned him to his parents. After Teyrnon told the story of how the child was found, Rhiannon was exonerated and again took Her place in the palace as Queen.

The story of Rhiannon teaches us that with truth, patience, and love we can create change no matter how bleak life seems at the moment.

Ideally, Rhiannon would be worshipped at night with Moon high in the sky, within a grove of trees, upon an Altar made from forest materials. In the real world, we can create an Altar to Her made of wood or stone, adorned with images of horses, birds, golden or white candles, and a bouquet of daffodils, pansies or pure white flowers. Soft music playing in the background would be a perfect offering to Her.

Call on Her to reveal the truth in dreams, and to remove the role of the victim from our lives. She teaches us patience, forgiveness and guides us to overcome injustice. She will aid us in magick concerning Moon Rituals, fertility, prosperity, divination and self-confidence.

In Britain, on September 18 people gather to scour the chalk of the Uffington White Horse. This ancient ritual has kept the image of the horse and the Legend of Rhiannon alive and relevant.

Andred

Andred is a little-known goddess of the pre-Roman British isles, whom the Romans referred to as Andraste. It was said by Roman historian Dio that she was invoked by Boudica before the Iceni rebellion of 60AD.

Boudica’s speech, taken from Roman History, by Cassius Dio:

Let us, therefore, go against them trusting boldly to good fortune. Let us show them that they are hares and foxes trying to rule over dogs and wolves.”

When she had finished speaking, she employed a species of divination, letting a hare escape from the fold of her dress; and since it ran on what they considered the auspicious side, the whole multitude shouted with pleasure, and Buduica, raising her hand toward heaven, said:

“I thank thee, Andraste, and call upon thee as woman speaking to woman; for I rule over no burden-bearing Egyptians as did Nitocris, nor over trafficking Assyrians as did Semiramis (for we have by now gained thus much learning from the Romans!), much less over the Romans themselves as did Messalina once and afterwards Agrippina and now Nero (who, though in name a man, is in fact a woman, as is proved by his singing, lyre-playing and beautification of his person); nay, those over whom I rule are Britons, men that know not how to till the soil or ply a trade, but are thoroughly versed in the art of war and hold all things in common, even children and wives, so that the latter possess the same valour as the men.

As the queen, then, of such men and of such women, I supplicate and pray thee for victory, preservation of life, and liberty against men insolent, unjust, insatiable, impious, — if, indeed, we ought to term those people men who bathe in warm water, eat artificial dainties, drink unmixed wine, anoint themselves with myrrh, sleep on soft couches with boys for bedfellows, — boys past their prime at that, — and are slaves to a lyre-player and a poor one too.

Wherefore may this Mistress Domitia-Nero reign no longer over me or over you men; let the wench sing and lord it over Romans, for they surely deserve to be the slaves of such a woman after having submitted to her so long. But for us, Mistress, be thou alone ever our leader.”

Lugh

For the Celts, who lived in central Europe, Lugh was a Sun god. The underworld god Balor was his grandfather. Balor was the leader of the Fomorii. The Fomorii were evil people that lived in the underworld.

According to a prophecy, Balor was to be killed by a grandson. To prevent the happening of the prophecy, Balor tried to kill his grandson, but Lugh miraculously survived. Lugh was secretly raised by the god of the sea ,Manannan, and became an expert warrior.

When he reached manhood, he joined the peoples of the goddess Dana, named the Tuatha De Danaan, to help them in their struggle against the Fomorii and Balor. Balor had an evil eye capable of killing whomever looked at it. Lugh threw a magic stone ball into Balor's eye, and killed Balor.

Lugh corresponds to the Welsh god Lleu and the Gallic Lugos. From Lugh's name derives the names of modern cities such as Lyon, Laon and Leyden. Today, people remember the figure of Lugh with a festival which commemorates the beginning of the harvest in August.

Greek Gods and Goddesses

credit: Anette Illustrations

Artemis

Greek Goddess of the Hunt, Forests and Hills, the Moon, Archery

Artemis is known as the goddess of the hunt and is one of the most respected of all the ancient Greek deities. It is thought that her name, and even the goddess herself, may even be pre-Greek. She was the daughter of Zeus, king of the gods, and the Titaness Leto and she has a twin brother, the god Apollo.

Not only was Artemis the goddess of the hunt, she was also known as the goddess of wild animals, wilderness, childbirth and virginity. Also, she was protector of young children and was know to bring and relieve disease in women. In literature and art she was depicted as a huntress carrying a bow and arrow.

Artemis was a virgin and drew the attention and interest of many gods and men. However, it was only her hunting companion, Orion, that won her heart. It is believed that Orion was accidentally killed either by Artemis herself or by Gaia, the primordial goddess of the earth.

In one version of the stories of Adonis – who was a late addition to Greek mythology during the Hellenistic period – Artemis sent a wild boar to kill Adonis after he continued to boast that he was a far greater hunter than her.